DIANA MARQUEZ HAS spent the last 14 months going on long walks, hitting the treadmill, and cooking with her daughter. She’s gotten to know her grandson, a fourth grader, helping him with his math homework. She has also lived with a weight hanging over her head — and an ankle bracelet strapped to her leg.

Marquez is one of roughly 4,400 people who were released from federal prison to home confinement starting in April 2020 as part of a Department of Justice directive aimed at preventing the transmission of Covid-19 in prison. Normally, the federal government allows people convicted of nonviolent crimes to serve out the last 10 percent or the last six months — whichever is less — of their sentences from home. Their time at home requires strict state scrutiny, including ankle bracelets and daily call-ins. The Department of Justice memorandum, issued under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, asked the Bureau of Prisons to relax the eligibility standards for home confinement so that people convicted of nonviolent crimes could leave prison despite having served less of their sentences.

The status of these people has been in limbo since December, when Justice Department officials from the outgoing Trump administration issued a memo stating that people whose sentences would outlast the Covid-19 emergency order would be returned to prison.

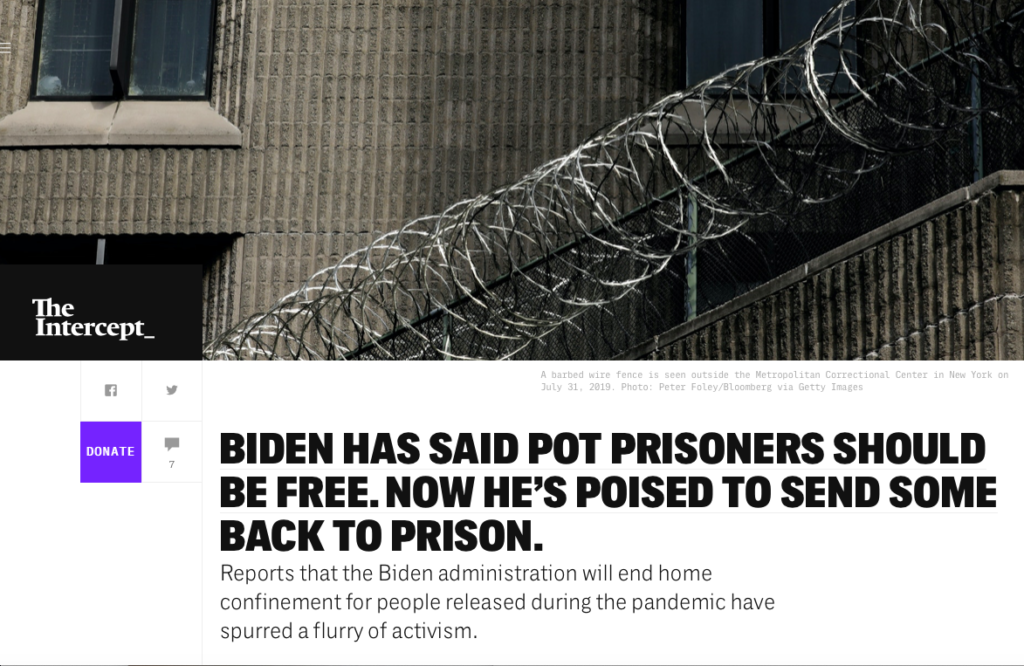

Last week, the New York Times reported that Biden administration lawyers had concluded that the Trump administration memo correctly interpreted the law — and that thousands of people in home confinement must be returned to prison after the yet-to-be-determined end of the “pandemic emergency period.” About 2,000 people stand to be impacted, with the rest having now completed enough of their sentences to qualify for early release under the standard guidance.

The Biden Justice Department’s position is especially shocking for people like Marquez who are doing time for marijuana-related offenses. President Joe Biden, after all, campaigned on loosening drug laws and said that people with marijuana records — who comprise a relatively small percentage of the federal prison population — should be freed.

“I don’t want to go back to prison, in the name of Jesus,” Marquez, who has served 16 years of a 30-year sentence for a marijuana conspiracy in which she played a supporting role, told The Intercept. She has noticed that during her time in prison, cannabis has become legal throughout the country. “Marijuana is already legal in 19 states,” she said. (Recreational marijuana is legal in 18 states and the District of Columbia.)

Barring executive intervention, Marquez and other people convicted of nonviolent crimes will be returned to prison, though no one can say when that will happen, due in part to resurging Covid-19 cases throughout the country and the prison system. Marquez is so stressed by the uncertainty that her hair is falling out in clumps, she said.

“They wake up every day terrified of going back to prison. Waiting is the hardest part,” said Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, which lobbies for more humane sentences and treatment of people behind bars. “And the administration’s silence is so callous.”

OVER THE LAST decade, states have taken the lead in legalizing marijuana, driven in part by the revenue needed to resolve annual budgets and the recognition that cracking down on pot and other nonviolent drug crimes does not increase public safety. But the federal government has lagged, clinging to an outmoded metric that categorizes marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug, in the same league as heroin.

As a presidential candidate, Biden was criticized over his opposition to legalizing marijuana. Responding to such criticism during a 2019 primary debate, Biden said: “I’ll be very brief. No. 1, I think we should decriminalize marijuana, period. And I think everyone — anyone who has a record should be let out of jail, their records expunged, be completely zeroed out.”

He said that it was important to study the long-term health effects of marijuana, but that did not change his stance about people serving prison time on marijuana charges. “That’s all it is,” Biden said. “No. 1, everybody gets out, record expunged.”

Yet since entering office, the Biden administration has been evasive on this question. In April, White House spokesperson Jen Psaki was asked how Biden planned to fulfill his pledge to free people serving time for pot-related offenses. Psaki stated Biden’s position on marijuana — “decriminalizing or rescheduling and certainly legalizing medical marijuana” — but did not directly address the question of clemency. “What you’re asking me is a legal question. Now we’re in government, and so I had to follow up with our legal team, and I don’t have any additional information quite yet.” The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Even as Senate Democrats have proposed a sweeping legalization bill and signaled that it is a legislative priority — 49 percent of Democratic voters are in favor of legalizing pot — Biden has yet to change his tune. Asked about the administration’s position on the legislation earlier this month, Psaki said, “I have not spoken with him in recent days about marijuana or legislation on this.”

The president’s waffling has frustrated advocates. “Biden said marijuana cases should be expunged,” said CAN-DO Justice for Clemency founder Amy Povah, who twice submitted a clemency petition to former President Donald Trump on Marquez’s behalf, the second of which remains pending. “So free them, and expunge it from their record.” Povah said she spoke to Biden’s White House counsel, lobbying for mercy for people in home confinement and reminding them about the president’s campaign pledge.

Given the high number of individuals in home confinement, evaluating each case would be a logistical challenge, so advocates are lobbying for an order of mass clemency for people sent home after the CARES Act directive, as well as for the pot prisoners he promised to free on the campaign trail.

But according to the New York Times, Biden’s team is wary of blanket clemency. Democratic presidents, historically eager to outflank Republicans as “tough on crime,” almost never grant commutations in their first term — certainly not mass commutations. They fear blowback if a person commits a crime after they’ve been granted clemency. During his first term, President Barack Obama pardoned 22 people and commuted one sentence. By comparison, Trump granted executive clemency to 237 individuals in his first term. Biden has yet to make any pardons or commutations.

Advocates point out that issuing mass clemency for people sent into home confinement who now face a return to prison is virtually risk-free: As the Bureau of Prisons director testified to Congress earlier this year, a mere 20 of 20,000 people out on home confinement were sent back to prison for violations of their parole. (That number includes people who were released under the CARES Act memo as well as people who were released because they were nearing the end of their sentence.)

“It’s such low-hanging fruit,” Ring said, noting that the releases were approved by then-Attorney General William Barr, an architect of the mass incarceration policies of the ’90s. “Whose sentence are you gonna commute if not these people? This doesn’t take a lot of bravery.”

THE NEWS OF the Biden administration’s interpretation of the home confinement decision spurred a flurry of activism, with #KeepThemHome trending on Twitter, as activists sought to pressure the president to grant mercy to the thousands of people who stand to be impacted.

Advocates have also used the conversation as a jumping-off point to discuss the arbitrariness of how decisions about home confinement are made. Take, for example, Raquel Esquivel, who was released to home confinement more than a decade into a 15-year sentence for helping smuggle marijuana across the Southwest border.

She was pregnant at the time of sentencing, and her son was taken away and given to her mother after his birth. When she was returned to home confinement, she tried to reconnect with her son, who is 11 years old, but it was tough, said her fiancé, Ricky Gonzales. “There was so much guilt there,” he said.

Esquivel, who is now six months pregnant, was sent back to prison in May after the Bureau of Prisons claimed that she’d missed a check-in phone call two months prior, which she denies. “They consider it an escape,” Povah said. “This shows the illogic of all this. She’s been calling in every single day. She’d done everything perfect, she had a job, she’s engaged, she’s pregnant. But they won’t back down.”