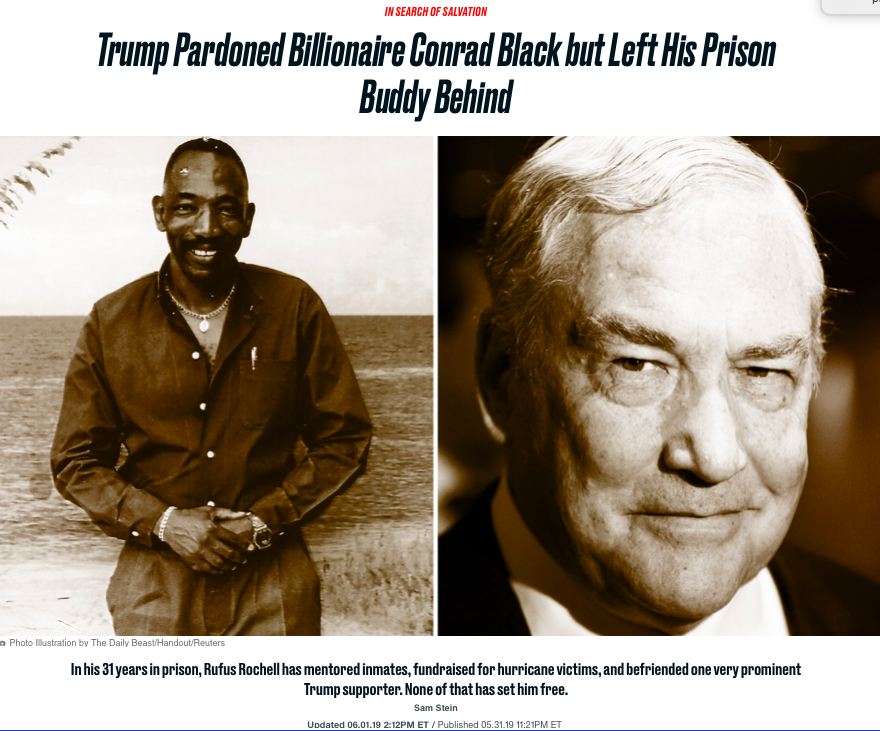

As he watched CNN from inside the federal correctional complex in Coleman, Florida, Rufus Rochell couldn’t suppress his joy at the news of Conrad Black. His old friend, the media tycoon with whom he shared a dorm years ago, had received a pardon from President Donald Trump. Surely this meant that his time would come soon.

Maintaining a level of optimism has been Rochell’s primary objective for 31 years now. That’s how long he’s been behind bars. He’s the byproduct of a bygone era when being tough on crime was viewed as politically savvy, when a man like him—a convicted drug dealer—could receive a sentence of 40 years and no one would think twice about the human cost.

But that was then. Now Trump himself was waking up to the injustices in criminal sentencing and surely Conrad Black, a Trump buddy, would help right his wrong.

“This is your old and forever friend Rufus Rochell, sitting here in prison for the many of years,” he wrote Black the day after the pardon was announced. “I saw on CNN today where the great president gave you a PARDON, that you truly and sincerely deserve. It couldn’t have happen to a better person… you now can go on with the family and be the great man you are and continue your journey to fighting for others like myself and other deserving ones that many have forgotten.”

Black was back in Canada, where he was born and had built his business empire, when his pardon was announced.

More than a decade ago, he had been found guilty of mail fraud and obstruction, charged with swindling his company of some $60 million. And in 2011, he had leaned on Rochell to help him secure early release by writing a letter attesting to his character.

Black’s sentence was ultimately shaved down on account of good behavior. And in the seven years after he was sprung from Coleman, he had resumed his status as a member of the upper crust and a commentator on world affairs.

He became an outspoken critic of America’s criminal justice system, owing in large part to his own experience. He also was a very public Trump booster, writing a book titled: Donald J. Trump: A President Like No Other.

The sequence of events led to questions about the judicial merits of the pardon. But when I reached out to Black shortly after the pardon was announced, it was with a different question in mind: Now that his record was expunged, would he help his old friend Rufus Rochell, as Rochell had done for him?

“I’m happy to write a letter of support for Rufus if they tell me where they want it sent,” was all he said.

But human interaction was what kept Rochell functional. He mentored fellow inmates, became a prolific letter writer, and posted book and movies recommendations to Facebook, often ones dealing with race or the criminal justice system. Mainly, he spent his time searching for his ticket out.

“He somehow got my phone number,” said Amy Povah, president of the CAN-DO Foundation, a group that advocates for greater clemency in the criminal justice system. “At first I tried to beg off. But he was so persistent and humble that I couldn’t ignore him. I said these calls are very expensive and money doesn’t come easy in there. But he just melts your heart.”